I sent this to Jose Estrella, following the tradition of ACC alumni of supporting each others creative endeavours (2 March 2020). This was one of the last few U.P. events I attended before the lockdown in March (13 March 2020). Posting this now because I was inspired by AAA's talk last night on "Art Criticism for the People" (17 Sep 2020). In so many words, it was implied in the AAA conversation that writing about art is a way to ensure its future life. It was eloquently explained how flash reviews that are done online immediately after seeing the work (in this case a play), is not any less important. It caters and responds to a particular audience in a particular platform with their distinct culture of meaning making. As an art teacher and an artist, this rings true and I feel compelled to respond. I feel tasked to be one of those who made sure art has its future, no matter the size or depth of the contribution.

***

HerStory: "Maria Rosa Henson, the first Filipina to reveal her story as a Japanese military sex slave during World War II. Nana Rosa covers her early years in Pampanga, to her capture during the war, up to her later years after coming out as a comfort woman in 1992." (from Facebook promo)

***

I came fully aware of the struggles and advocacies of comfort women. It was a subject favoured by many of the artists and scholars I have worked with recently. It was even the core of a conversation I moderated for MonumentED, a traveling performance festival, advocating participation of creatives in monumentalising the stories/ struggles of the comfort women. MonumentED is curated by Japanese-Canadian, Daisuke Takeya.

Anyway, I am writing to share with you my thoughts about Nana Rosa, your play. The whole play was captivating from the first minute to the last. Besides the story, the storytelling proved to be compelling in so many accounts.

The monologue needs no mentioning anymore, as a fine actress such as Peewee O’hara is expected to deliver (and she did) a very moving performance.

My interest rests on the other devices of storytelling. For example, the use of lights—whether from spots or the projection. One scene that made a mark was the first time the Task Force ladies came out on stage. Light casts on one side of their faces, while the other half was hidden in shadows. The long shadows of their bodies formed a distorted version of their communing projected on the wall. There are many other interesting uses of lights in the whole play, but that one in particular was remarkable.

Sound, as my specific interest, was equally compelling. The simple feet stomping, the act of striking the feet loudly on the floor, was translated in the play as several things. Soldiers’ marching signals doom. Scrambling of the women’s feet, which was between stomping and dragging, declares fear and tribulation. And the stomping in the protest during the last scene echoes the heartbeat of a people power.

The three scenes in one: (somewhere at the beginning) when Nana Rosa was writing, the young Rosa and her mother at the centre stage were in hysteria, and the Task Force on a radio programme (behind a screen). In this scene, the intimacy or distance of sound determined the distance of the sound producers to the story being told—Nana Rosa as the present her, was subtle but unmediated; she sounded as if she was talking to the audience. Young Rosa was screaming, as if (or because) she was coming from afar (long time ago). And the sound from the radio had that broadcast quality, something that is mediated and recapitulated by technology.

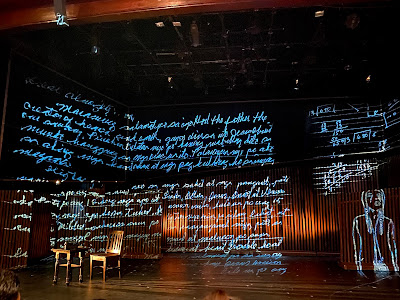

The generous use of projection cannot go unnoticed. It had served its aesthetic purpose as it made the play more dynamic. It had served a practical purpose as it contained historical references, translations, among others, without obscuring the set design. And it had made the story current—a history that is now, rather than simply something that is old or from the past.

These were some of my thoughts. The rest of the time instead of appreciating the craftiness of how this play is staged, I became busier tempering my emotions—I didn’t want to contribute to the sobbing and gasps, which at some point was already hard to determine, whether it is from those on stage or coming from disconcerted audience. The sobbing and gasps punctuated what was otherwise a very well-designed storytelling. This confirms how much we are all affected.

Again, thank you for your beautiful work and for reminding us not to forget.